5. Youth housing

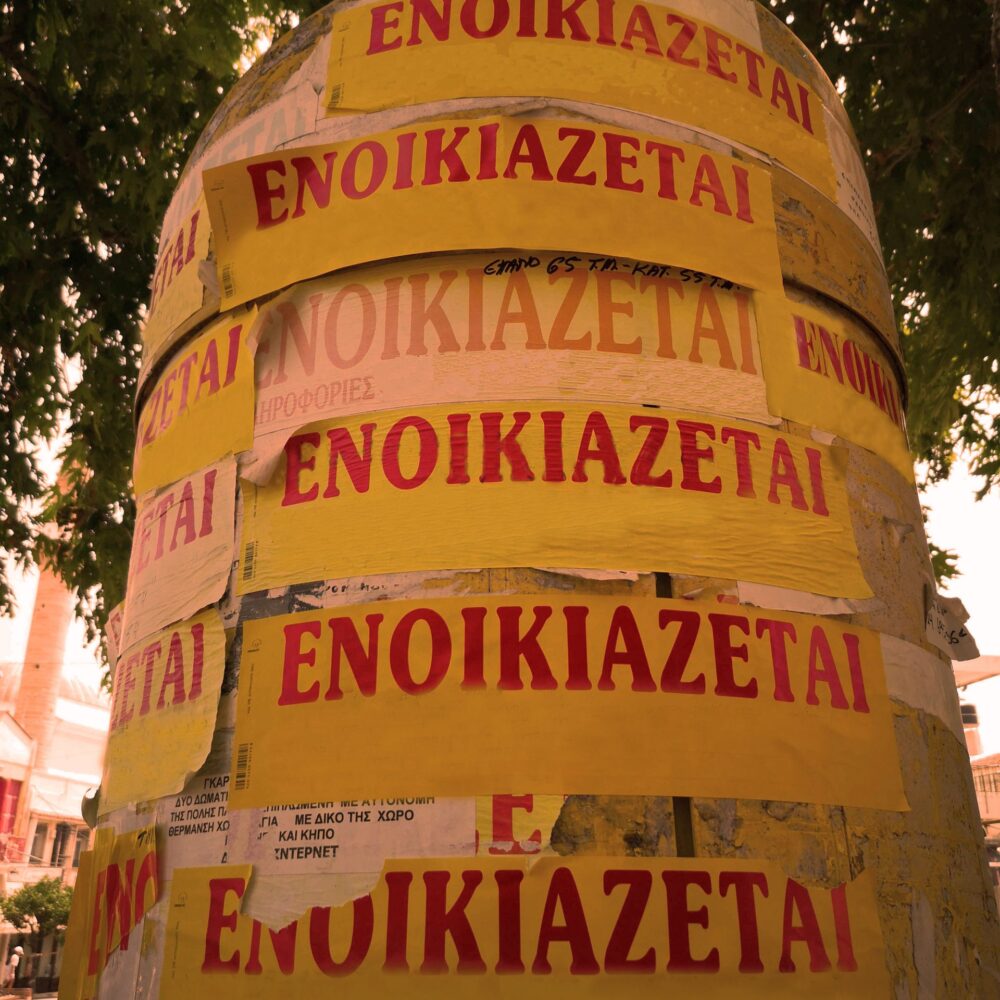

Young people are finding it increasingly difficult to meet the rising housing costs and are forced to live in poor housing conditions or continue depending on their parents.

A. The young are the main victims of the housing crisis

Young people are the social group that is most affected by the increase in renting and housing costs that has taken place in the past few years.

Moreover, the increasingly small number of properties that are available for rent and the deplorable condition that most of them are in, render access to independent housing even harder and force young people to accept living in terrible housing conditions.

The age of emancipation from the family is pushed back, as young people live with their parents longer than they used to, are often forced to return to the family home (boomerang kids), and depend on parental contributions in kind and money for their housing.

They have less access to home ownership and greater dependence on rental housing (generation rent), often resorting to the (not so popular in Greece) option of cohabitation in order to cover costs.

They are most affected by housing costs, as they are in the worst position within the labour market, generally receiving lower wages, in more precarious and insecure jobs, with high rates of part-time and flexible employment, and face some of the highest unemployment rates in Europe.

The existing social security measures to support young people who are taking their first steps towards their goal for housing independence are limited and insufficient.

According to a recent report published by FEANTSA, the number of young people that are facing the risk of housing exclusion is increasing, since the dramatic disconnect between housing costs and incomes has a disproportionate impact on young people’s living conditions.

Despite the important role of intergenerational solidarity, which continues to be the main pillar of social protection for young people in Greece, the limited opportunities for self-sufficiency of the new generation reinforce the dependency and the entrapment of young people.

B. Young people in Greece face increased housing difficulties

According to Eurostat’s data for 2020, young people in Greece will leave their parents’ house when they’re 29.6 years old, on average (in 2010, the respective age was 28.3 years old).

Women will move out at the age of 28.4 while men will do so when they’re 30.7 years old. The European average is to leave home at the age of 26.4.

At the same time, during the recession, there has been a significant increase in the percentage of young people aged 25-34 who were still living with their parents. It rose from 50.6% in 2010 to 62.2% in 2020.1

34.3% of young people aged 25-29 are overburdened by housing costs (while the EU average was 13.3% in 2020) (Γράφημα 3 ή 4) and 42.5% live in conditions of housing overcrowding housing deprivation (right behind Romania: 58.7%, Bulgaria: 56.4%, Latvia: 51.1%, Croatia: 48.2%, Poland 47.3%, while the EU average was 22.5% in 2019).

Graph source: Dewilde, C. 2020

The increasing difficulty for young people to access homeownership is also reflected in the data of the Hellenic Statistical Authority’s (ELSTAT) Survey on Household Income and Living Conditions, as the share of young homeowners decreased significantly between 2005 and 2017.2

Especially in the case of the refugee and migrant population, a very high percentage of unaccompanied minors residing in Greece live in precarious housing conditions. Their coming of age is accompanied by stress as young refugees face even greater difficulties in finding work and thus in accessing a stable income to cover housing costs.

Similarly, young (second generation) immigrants continue to face widespread discrimination, inequalities, xenophobia and racism.

C. Unemployment, precarious working conditions and dependency

In the context of the family-oriented southern European social model, young people in Greece depend heavily on the family to cover their housing needs, staying longer in the parental home or with relatives, or receiving financial support in order to be able to cover the cost of an independent dwelling, while intergenerational transfers also play a decisive role in the acquisition of a first home (through parental donation or bequest, transfer or inheritance).

In Greece, just like in Europe, there is an increasing polarisation tendency between those within the social protection system, who own their own home and have a supportive family environment on the one hand and those who don’t on the other (insiders-outsiders dynamic).

The housing production mechanisms that were passed down from generation to generation in Greece, although until recently maintained social and upward mobility and ensured social cohesion to a certain extent, can no longer function.

Since most households’ capacity to support their younger members is becoming more and more restricted 3 and access to home ownership through mortgages is getting harder, young people increasingly depend on rental housing.

All of the above are directly linked to the gradual deregulation of the labour market and the devaluation of labour costs, which particularly affects young people, hampering their economic independence and creating a broader context of economic hardship.

Greece has the highest youth unemployment rate in the EU (ages 25-29). The relevant percentage was 27.2% in 2020 (with the EU average being 10.3%), which is significantly lower than during the recession (43.3%). Still, it has increased from 2019, before the Covid pandemic, when it was 25.8%.

Young people’s income fell by 40% during the recession – more than any other age group of workers.4 The young are generally paid the lowest level of wages and are unable to cover their basic needs.

Young people are more exposed to the precarious working conditions that have been prevalent and normalised by the flexibilisation of the institutional framework. According to research carried out by the University of Crete, underemployment, part-time/seasonal and other flexible forms of labour5 have increased dramatically, thus increasing the marginalisation and social vulnerability of young people.

Moreover, as reflected in a recent Eurofound study on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on young people in the EU, Greece comes first in the percentage of young people (15-29 years old) who found themselves out of work during the pandemic, reaching 30% and at a significant distance from the rest of the EU countries (with Spain coming second, with a rate of 12.1%), thus reflecting the high job insecurity that young people are facing. Despite the occasional mentions of the problems that young people are facing and the need for policies that would need to be implemented in order to keep and encourage the repatriation of scientists, no substantial measures have been adopted.

D. Providing substantial support for the economic and housing independence of young people

The EU has, over the past years, issued guidelines and directives for the development of policies concerning young people, with no particular focus on the issue of housing. Still, the increase in the number of young people who are experiencing housing insecurity and/or homelessness is a development of growing concern to organisations working around the issue of housing in Europe.

In addition to the FEANTSA report that is sounding the alarm regarding youth homelessness rates in 2021, Housing Europe published the “Housing the EU Youth” Research Briefing in 2018, while detailed policy proposals on youth housing have been developed in the UK (e.g. by Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Rugg – Quilgars 2015).6

The issue has often found itself at the centre of public debate in Spain, with the most recent development being the enactment of the rent subsidy for young people up to 35 years of age.7

In Greece, the focus of public intervention (and investment) has always been on supporting the purchase of primary residence (which should be exempt from real estate transfer tax)8 and the low taxation of parental bequests and donations for the acquisition of primary residence.

After 2019, several young people with zero or very low income benefit from the rent subsidy9, and finally there is also a student housing benefit for the duration of one’s studies.10

At the same time, for-profit business activity in student and youth housing (PPPs for student residences, rented apartments, coliving 11, etc.), has started to be developed in Greece – a rapidly growing sector in other European countries.

Support for young people has been at the epicentre of recent announcements by the government (for young couples)12 and the opposition (rent subsidies for young people). However, the need for a long-term housing strategy for young people and, more broadly, a strategy that would support their emancipation and independence has not been put on the table yet.

The challenge is therefore to develop a comprehensive framework to support young people taking their first steps into the labour market and on their path towards independent housing. This framework should also include the promotion of collective and cooperative non-profit housing models. Such models are obviously not only relevant for young people, but they certainly represent a social group that is more open to alternative formats and experimentation with new ways of living.

4. Vacant houses

4. Vacant houses